In early September, we reported on an innovative approach to online music collaboration adopted by the Ragazzi Boys Chorus to allow the organization’s various ensembles to keep rehearsing during the pandemic-mandated limits on gatherings. Ragazzi was the first music group to use “Virtual Studio,” the hardware/software solution developed by the JackTrip Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to helping musicians collaborate remotely.

The particular problem Virtual Studio addresses is limiting the latency (delay) in audio signals that plagues most groups that attempt to make music online in real time. As most of us have experienced, even basic online interactions via Zoom and other interfaces frequently involve hiccups in the signal and little delays and gaps that can make conversations challenging and making music in synch virtually impossible. JackTrip technology combines a simple piece of plug-and-play hardware with a remote virtual server to greatly reduce that latency and the resulting audio hiccups.

Results of the initial testing two months ago seemed very promising, and we noted in the article that there were plans to make this technology available to everyone as soon as possible. Interest in the story was immediate and widespread, and we received many queries wanting to know more, particularly from music organizations hoping to adopt the technology for their own online rehearsals. We promised to report back when more information was available.

This week I met via Zoom with Alan Hu and Russ Gavin, two JackTrip Foundation board members, to discuss progress with the project. With a Ph.D. in music education and as director of the Stanford Band, Gavin is particularly qualified to talk about the practical application of the technology.

According to Hu, the Ragazzi rollout has been meeting expectations, and more. “We have three choruses on there now, and we’re rolling out to a fourth this week. Each chorus is about 40 boys. We started with the older boys, added the next younger groups, and this week we’re adding the 9 to 10-year-olds. That says a lot, because we’re trusting very young boys to use this. The largest group we’ve gotten together so far is 80 boys. It’s phenomenal.” You can see the video of the 80-member chorus rehearsing below.

Hu says that their projections regarding latency are holding true. “We tend to talk more about how far away you can be rather than about ‘latency,’ which is kind of a foreign concept. We say ‘we don’t want you to be more than 300 miles,’ but we’ve tested much further than this. We’re not giving that as guidance, but it’s promising.” He went on to relate anecdotes about choristers logging in from as far away as Mexico with tolerable latency that enabled them to participate.

“The technology is holding up very, very well. The issues we tend to get are with the internet infrastructure: poor service on a particular day or a bad connection, rather than with the JackTrip technology,” said Hu. In terms of the specific latency they are marking, he says that it is between 17 to 23 milliseconds for most users, which is still perceivable to some, but within the tolerances of what’s practical. But for many, it’s better than that. Gavin adds, “It can be as low as 6 milliseconds, if you have a great internet connection. I average about 13 personally with my setup. A lot of our kids are getting that good range, too, in the Bay Area, anyway.”

As promised, the JackTrip Foundation has made its technology available to anyone, and the JackTrip folks think it has potential far beyond the obvious chorus market. “Our market is anyone who likes making music, period,” says Gavin. “We’ve seen success with weekend rock combos with three members all the way up to the San José Youth Symphony. We had somewhere between 80 and 100 symphony musicians connected last Monday.”

At the other end of the scale, the scheme works great for smaller ensembles. Gavin says, “String quartet, trio, duo. The University of Oregon is testing it with instrumental soloists and accompanists.”

So how can a music ensemble take advantage of this opportunity and get their own Virtual Studio setup?

Because the open-source software itself is free and available to the public for download and there are instructions for building the hardware interface at home, a tech-savvy group or individual could set themselves up. For the rest of us, there are two main pieces to the puzzle.

First is the home/hardware side. Users will need a way to connect a microphone and headphone to their modem via an ethernet cable. Technophiles and hardware junkies may feel at home building their own interface — there are instruction online for doing it on the cheap — but JackTrip has a plug-and-play Virtual Studio interface available for purchase. Contact [email protected] to purchase the device. Cost is $150 for the device itself.

Depending on what kind of sound gear, cables, adapters, and widgets you have around home, that might be the only real expense. In addition to the interface, users will also need an ethernet cable to connect the Virtual Studio device directly into the modem (not into a Wi-Fi extender or mesh — hardwire to the internet router or switch), headphones with an RCA-to-3.4 mm jack, a microphone with a cable and adapter ending in a 3.5 mm plug, and a USB-C power supply. I have all that stuff kicking around home already, but the JackTrip site has an article about acquiring all of the recommended accessories for as little as $50.

Click here to get basic information about setting up a basic JackTrip setup at home. This bare-bones approach can be enhanced to any gearhead’s delight with preamps, mixers, phantom power for a condenser mic, an interface such as a Focusrite Scarlett, and a setup for real-time, CD-quality recording, and so forth, depending your interests and abilities.

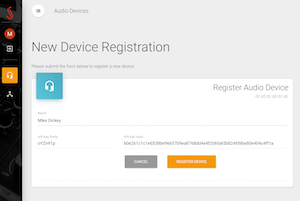

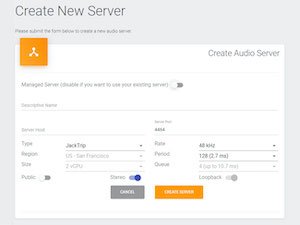

The second piece of the puzzle more or less takes care of itself once you have successfully connected all of the above. Using your computer, you log into the JackTrip site to register the device and set up a virtual server. Gavin demonstrated the process for setting up a new server for an imaginary project for me during our Zoom meeting, and the entire process took less than a minute. “The interface is simple enough that even some fool like me can do it,” said Gavin. “It was built for musicians so that it would be absolutely approachable.”

The dedicated JackTrip server is essential to the whole concept, and again, it’s possible for enterprising DIYers to set up their own server, but JackTrip is providing virtual servers for five initial regions during the Beta phase of the program. There are currently servers available for San Francisco and Los Angeles in California; Portland, Oregon; Ashburn, Virginia; and Dublin, Ohio.

Upcoming phases will introduce more servers around the country, with a long-range plan for further expansion. See details about the managed servers here. Server access is free as of this writing, although there may be modest charges based on group size applied once the Beta phase is complete.

That’s it, really. The hardware and server setups are intended to be straightforward and user-friendly, and, because the JackTrip Foundation is a nonprofit, relatively inexpensive. Gavin explains, “once onboarded correctly with the good home internet and all the things we say are needed, it quite simply works. That’s the big takeaway from the students and the teachers using it.”

One thing for users to bear in mind is that this solution is for audio only. Any visual connection will still be by way of Zoom-style videoconferencing, and there will not be the same kind of improved synchronicity with the video component. That might seem like a downside, but He and Gavin suggest that there’s a something of value in divorcing the senses in this context.

“As with any new technology there are things you have to do differently,” says Hu. Without a conductor in the room, members of larger groups have to compensate in new ways. Some are electing to add a metronome, others are choosing to follow a specific musician in the mix. Gavin adds, “Everybody’s ears just have to get better ... I’m excited about the long-term applications of this because it just makes us have to be better individual musicians turning on our aural sensitivities in the rehearsal environment, where normally I might think, ‘I’m going to use my eyes to figure this out.’ No, we’ve got to use our ears now. I think that’s got a lot of pedagogical value, now and after the pandemic.”

CORRECTION: Typical latency for Virtual Studio users 17 to 23 milliseconds, not 25 to 30, as was stated in the story as originally published.