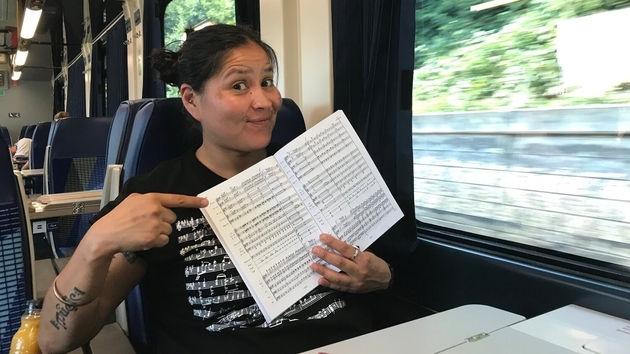

Before you go the inaugural concert of the newly created San Francisco Philharmonic, at the War Memorial’s Wilsey Center on Feb. 3, conductor Jessica Bejarano would like you to know something about one of the featured composers and herself. Their lives are linked by more than just music.

“When I found out Tchaikovsky was gay, there was an instant connection between me and him,” says Bejarano, during a long interchange in a café in the Castro District, near her San Francisco home. “His Fourth Symphony,” one of three pieces on Monday’s program, “is known as the ‘Fate’ symphony. It was meant to be. And when I went back and listened to this music, I could hear the anguish, the despair, the yearning, the instability, and the love. It was his only vehicle of expression.

“Music was that for me too,” she continues, “because when I was younger — growing up poor, growing up Latina, growing up gay — the only thing that kept me anchored was music. If you know these things about a composer or a conductor, then you are that much more connected, you have more understanding of their music.”

Bejarano, now 39, was born and raised in Southern California by a single mother, Maria, whose own mother had immigrated from Tijuana. “My mom worked three jobs, and at one point, when I was in school, she would trash dig, to find cans and bottles to recycle,” says Bejarano, who attended Bell Gardens High School, a few miles south of East L.A. “It had one of the highest teenage-pregnancy rates, and also one of the largest dropout rates.” But it also had a marching-band program, and young Jessica, who’d been introduced to trumpet by her older brother Rigoberto, was one of its stars.

“I was not exposed to classical music at all,” she notes, “but in fifth grade I was taught to read music. Every year the high school had a new music director, because the school was out of sorts, and every time a teacher would quit, I would have to teach the class. I loved being in leadership roles, and that’s when I started conducting.”

Bejarano’s family was proud, and a little surprised, about her excelling in music in public school. An embrace of her budding sexual identity was less forthcoming. “I don’t think there was a moment when I was, ‘I’m out, I’m gay!’ But I was close to my girlfriends, and at some point, they started chasing boys, and I just never did that. Then my brother outed me to my cousin, and one of my cousins outed me to my mother. My family did not accept it, and it took many years for them to get over it. But they did.”

Music education was the obvious major waiting for Bejarano at Pasadena City College. She continued with trumpet, and a friend recommended she audition for the Troopers, a world class competitive drum-and-bugle corps based at Casper College in Wyoming. “I marched with them for a year, they offered me a full-ride scholarship.

“Everyone there called me ‘Hollywood.’ I was working on my degree in music education, and I did residencies where I had to go into a middle school or high school, just to get the hands-on experience of working with children. And one of my mentors looked at me and said, ‘How are you going to stand in front of children, looking the way you do?’ At that point, aside from having tattoos, I had 13 piercings on my face,” she chuckles. “I said, ‘it doesn’t matter what I look like, I know the material, and I know how to educate, motivate, and inspire music in those kids.’ When I try to pretend, or to hide things about myself, it just doesn’t work.”

Transferring with a full scholarship to the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Bejarano finished her bachelor’s degree in music education. A year’s course in conducting, which she finished at the top of the class, had convinced her that her best position was on the podium. “I didn’t look at the statistics of females in the field of conducting,” she recalls, “and I’m glad I didn’t, because there wasn’t a large history of that at that point.”

She found Laramie surprisingly supportive of her sexuality. “Matthew Shepard had just been murdered a few years before I arrived [when he was a gay student at the University, in 1998], and there was a huge movement for the gay community. Ellen DeGeneres came there, Elton John came there, so there were parades, marching, socials, special gay nights at bars.”

Yet another full scholarship, to the University of California at Davis, allowed Bejarano to return to California and work toward a master’s degree. “I was told they had a fantastic choral conductor, but that the orchestral conductor (I prefer not to name him) was a misogynist. I still went.”

She found a campus that was “unique, in that their venue [the Mondavi Center] is a world class concert hall, with a history of a great orchestra. The caliber of the musicians, who included students and some community members, was stellar.” But the notorious conductor and faculty member rendered rehearsals hellish. “He’d say, ‘Get on the podium, hurry up!’ Then he’d sit right next to me in a chair, arms crossed, slouching. He’d make fun of my gestures, make fun of my body. It was abusive to the point that the musicians would come up to me and apologize for him.”

Bejarano says the professor’s “knowledge of music was impeccable, and I wanted that,” but one of their score-study sessions was interrupted by his abruptly questioning her seriousness about the program. “I told him I was all in, 100 percent! And he went on to say, ‘well then, maybe you should go back to your country, because it’s not going to happen in mine!’ I thought it was a joke. I was waiting for him to start laughing, and instead he pointed at the door and said, ‘get the fuck out!’

“I went home and stared at the wall for, like four hours. And I remember thinking, if this is how academia is treating me, what is the real world of the orchestra going to be like? I told myself, ‘I’m done.’ But five seconds later, I was, ‘Jessica, what are you doing? Don’t allow someone to take away something you want, to take it out of your life.’”

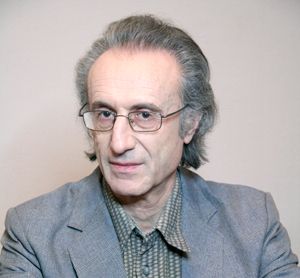

Between the two years of the master’s program, Bejarano studied at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg with conductor Leonid Korchmar, with whom she’d workshopped in Wisconsin. “With him being Russian and me writing my master’s thesis on Tchaikovsky, I thought it was perfect to be in the city where Tchaikovsky had lived. Before I went there, they gave me a list of things not to do in Russia: Don’t drink water out of the faucet, watch out for gypsies, on transit keep your bags close to your person. On the same list was: Don’t look gay, don’t act gay, don’t be gay. I was like, ‘that’s not fun!’ And the experience was incredible, I was extremely well taken care of. I knew that I had to do these kinds of other things, because having a master’s degree in conducting was not going to get me really far.”

Bejarano’s mother Maria attended her master’s thesis performance at Davis, “and she was absolutely blown away! My dream was to graduate, get a great job, and one day knock on her door and tell her, surprise, today is your last day of work, I’m going to take care of you for the rest of your life, you’ll be able to sleep in!”

The following summer, Bejarano studied with several conductors in Europe, and returned to the States with an acceptance to the DMA program in orchestral conducting at the University of South Carolina. A friend had badgered her into also applying for an assistant conductor’s position with the Peninsula Symphony (based in Los Altos). She took that job after some amount of negotiation and self-examination.

Turning away from academia and toward the professional life, Bejarano started paying more attention to the status of women on the podium. “I was looking through this gay magazine called Out, and there was a picture of this female conductor, Nan Washburn [of the Michigan Philharmonic] in tails, with a red cummerbund, red bowtie, and short curly brown hair. That was the first image I had that cued me into, ‘a female can do that!’”

Later, for her own profile in the lesbian magazine Curve, Bejarano gave a shoutout to conductor Marin Alsop as an inspiration. “I applied to any and every workshop Marin ever gave, I got to work with her at the Cabrillo Festival and in a Baltimore Symphony workshop. She has so much presence and command, she’s such a badass, that woman! I still email her when I have questions about repertoire.”

Committed to the Bay Area, Bejarano “just started hustling, trying to get experience. I’ve been with the Bay Area Rainbow Symphony, the Community Women’s Orchestra, the West County Winds, and the VOICES: Lesbian Chorale Ensemble. And I ended up as the main director of the San Francisco Civic Symphony. I remember someone once making the comment to me, ‘you got this or that position because you’re a lesbian.’ And I remember replying, ‘no, no, no, I got those positions because I’m great at what I do, not because I’m great at being a lesbian.’”

Her work in Northern California allowed for holiday visits back home to Maria, who was working as a janitor in a casino in Bell Gardens, in the L.A. area. “I would go to her work, and she would parade me around.” In 2012, her mother suffered a brain aneurism that ruptured and put her in a coma. Bejarano went to Maria’s beside and “played the Adagio movement from Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto in her ear, from my iPhone. It had always set the tone of the day for me. I thought, if it saved my life, it could save hers, miracles happen. But ultimately, she passed away, on Mother’s Day. I got so upset with music. ‘How dare you!’ So I took a break, I didn’t listen to it.

“I decided to become a police officer. I applied to the San Francisco Police Department, took the written exam. Then there was an obstacle course, and after that, you’re a cadet. But I couldn’t jump over the wall! They said, you’re disqualified, you need to come back in six months.

“But sometimes when something seems a wall or a barrier in your life, it can actually be a blessing. I needed income, so I started teaching at Alta Vista Elementary School. I was wary about getting back into music, but after school one day, one of my piano students said, ‘I’m going to draw you a superhero.’ She drew a ballerina with a little tutu, midair, arms up. And I said, the ballerina is a superhero? She said, no, ‘you’re the superhero, because you make music, and you make the ballerinas dance!’ That 5-year-old melted my heart! I went back to music full-force, and I felt alive.”

Also reawakened was Bejarano’s dream of someday leading a top-tier orchestra. “If your career is not turning out to be what you wanted it to be, based on other people’s decisions, turn it around and put in your own hands, and make it happen. Start your own orchestra!” One of her role models in this regard is Nicole Paiement, who recently engaged the younger conductor as an assistant on Opera Parallèle’s upcoming production of Harvey Milk.

“Already, Jessica’s generous spirit, her curiosity, and her obvious musicianship have been appreciated,” states Paiement. “She has a warm, charismatic personality, and works hard.” About Bejarano’s “own orchestra,” the brand-new San Francisco Philharmonic, Paiement points out that, “this will add a great deal of work to Jessica’s schedule aside from score study and music making, but in the end, it will be more representative of who she is as an artist. We need a variety of arts organizations, and I’m sure hers will be adding a great layer to the fabric of this community.”

The Philharmonic’s four-score musicians have had several rehearsals and “they’re sounding amazing,” enthuses their conductor. The first of their inaugural season’s three concerts next week will feature SF Symphony principal violist Jonathan Vinocour and SF Ballet concertmaster Cordula Merks in Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, selected by the soloists. “We’re offering the community an opportunity to witness Cordula and Jonathan out of their chairs, in front of an orchestra, playing a concerto at a very affordable price,” says Bejarano. The Mozart shares the bill with her beloved Fourth Symphony of Tchaikovsky, and Mendelssohn’s “Hebrides” Overture. Op. 26, recommended by her woodwind section leader.

The Philharmonic’s second concert, on April 11, will feature Gallia Kastner, concertmaster of the American Youth Symphony, in the Beethoven Violin Concerto, and a third, on June 3, will offer Beethoven’s Triple Concerto, with Miles Graber, Sarah Wood, and Nora Karakousoglou. Complete programming will be announced later on the orchestra’s website, and tickets are available through the website, Eventbrite, and the Philharmonic’s Facebook page.

Bejarano still sees music education as a powerful platform. “I’m a role model,” she says, “because whether I’m gay, whether I come from poverty, whether I have immigrant parents, I could still achieve that. If you can see it, you can be it.” She’s on the faculty at University High School, where her students “are excited about the Philharmonic, they’re buying their tickets and will be going with their families. The more I grow, the more I learn, the more I’m able to give them.”

“Jessica has not only guided and inspired her orchestra students to perform challenging pieces,” testifies James Faerron, the school’s arts-department chair, “but she’s also shined as an example to those who fear they may not be able to reach their dreams, because of who they are and where they come from.” Bejarano also directs youth orchestras in San Rafael and Salinas.

The Philharmonic has so far been funded mostly out of its founder’s pocket. Except for the concertmaster, ensemble members are playing for free. But the board of directors is applying for financial assistance, and individual donors and sponsors are encouraged to contribute at the orchestra website, Facebook page, or by emailing [email protected]. Musicians are invited to request an audition.

Bejarano’s storied determination has already won her profiles on the PBS News Hour and the Today Show, and on Friday, Jan. 31, she was heard on “The State of the Arts” segment on classical music station KDFC. The website of the international Conductors Guild, earlier this month, praised Bejarano for founding the Philharmonic, with the message, “And they say orchestras are dying? Not!!”